32BBTW, what's the size of the full largest version of Qwen-Coder? Is it 32B? Or is it 70B? This is the model I'm most interested in at the moment for running it in my also new M4 Max Studio with 128GB. I have not tried to run LLMs yet because I want to first build llama.cpp myself (I'll be using llama.cpp only, I'm a C/C++ guy --besides, if something works in LM Studio, it must also work in llama.cpp if the proper settings are used).

Got a tip for us?

Let us know

Become a MacRumors Supporter for $50/year with no ads, ability to filter front page stories, and private forums.

M4 Max Studio 128GB - LLM testing

- Thread starter JSRinUK

- Start date

- Sort by reaction score

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You say "128GB on an M4 Max is of more use to me than 96GB on an M3 Ultra, I feel," which makes total sense. But why would anyone buy an M3 Ultra and hamstring it with only 96 GB RAM when 500 GB is available? IMO in addition to GPU cores of course, the point of an M3 Ultra purchase would be for the available additional RAM and memory bandwidth. Especially for LLMs. Serious question, because I currently have an M2 Max with 96 GB RAM.I’d love to be in that field. I’ve seen how much Nvidia GPUs go for and can only imagine what the cost must run to get a system with sufficient VRAM.

This is why I’m amazed at what we can actually do with the Mac Studio (I go back to the ZX81!). I’m always trying to push to the edge of what the machine I have is capable of. (I still recall pushing that old ZX81 to fill up its 16K RAM pack - for no better reason than “I have to try"!)

For context, my budget for my Studio was originally around £3,200 - and I was kind of hoping 128GB would come in around there. Pushing to £3,800 for 128GB (plus 1TB SSD) went right to the edge of my comfort zone. If the M3 Ultra had started at 128GB, I may *just* have pushed to the £4,200 price (but I’d be arguing with my bank balance every step of the way).

In the end, I’m happy with what I have. 128GB on an M4 Max is of more use to me than 96GB on an M3 Ultra, I feel. I think it’s the right Studio for where I’m at right now. Spending more would just put me in a struggling position financially and, for what amounts to little more than a “hobby” combined with “learning experience” right now, I can’t justify that.

Last edited:

I think you’ve nailed it there. For me, if the M3 Ultra base model had come in with 128GB and was the same price as the base model with 96GB is now, I might have squeezed the extra to pay for it (the extra cores would be worth a couple of hundred quid more). I couldn’t go any more expensive than that, because I’m already at the edge of my budget (for me this is currently more of a hobby to feed my “computer-geek” inner self). Any pricier and it gets too uncomfortable. Going to the next level up (256GB) is well out of my league, and the cost for 512GB is just some other planet.You say "128GB on an M4 Max is of more use to me than 96GB on an M3 Ultra, I feel," which makes total sense. But why would anyone buy an M3 Ultra and hamstring it with only 96 GB RAM when 500 GB is available? IMO in addition to GPU cores of course, the point of an M3 Ultra purchase would be for the available additional RAM and memory bandwidth. Especially for LLMs. Serious question, because I currently have an M2 Max with 96 GB RAM.

If I was in the position that money wasn’t my primary concern, I’m with you - the M3U with 512GB would be a beast, and it would be all I’d be looking at. 96GB makes no sense. I also don’t understand the purpose of the base M4 Max Studio with just 36GB RAM either. I’m guessing they just want to hit a price point to tempt those who are looking at the Mini with upgrades, but I still don’t understand who’s buying it.

The base M3 Ultra Studio is fine with 96GB of RAM for those who are just going to have it sit and do video all day. There are people who just need to do video production, and 96GB is fine for that job.I’m guessing they just want to hit a price point to tempt those who are looking at the Mini with upgrades, but I still don’t understand who’s buying it.

Agreed. I've had the base M3 Ultra for about a week now and it's been fantastic at the video work I've thrown at it whether it's Blender, After Effects, Premiere or Topaz Video AI. Since I'm not focused on using LLMs that much, 96 GB RAM has been sufficient so far for my needs.The base M3 Ultra Studio is fine with 96GB of RAM for those who are just going to have it sit and do video all day. There are people who just need to do video production, and 96GB is fine for that job.

You missed the previous sentence that provided context to the one you quoted, re:The base M3 Ultra Studio is fine with 96GB of RAM for those who are just going to have it sit and do video all day. There are people who just need to do video production, and 96GB is fine for that job.

I totally get that if you need all the extra cores and you’re being price-conscious, the 96GB M3U hits the spot. If the sacrifice of 32GB of RAM for the extra cores works for you then, of course, it’s the right machine for you. For my use case, LLMs/AI, I wouldn’t want to sacrifice the RAM for that. That’s all I’m really saying.I also don’t understand the purpose of the base M4 Max Studio with just 36GB RAM either. I’m guessing they just want to hit a price point to tempt those who are looking at the Mini with upgrades, but I still don’t understand who’s buying it.

I haven’t done a lot of model-comparison just yet. My aim for this machine was to use the largest model I can with a decent context-length and without heavy quantisation (hence Q6, not Q4), and that’s kind of what I’ve been focussing on.@JSRinUK -- so now that you've had your studio for a bit, which models are you going back to again and again?

With the recent Gemma 3 and Mistral 3.1, I'm wondering if I should just grab a 64gb Mac mini and call it a day, or keep my options open get a the Studio that you've got.

At the moment, my 128GB Studio hits its limit using the 104B model quantised to Q6 and a max context length of 32,000 (when using llama.cpp - closer to 25,000 if using LM Studio with guardrails removed). With other system processes and apps, I see Memory Used at up to 120GB of the 128GB - but, most importantly, no swap.

Ollama seems to have an issue downloading models for me at the moment, so I’ve not been looking at different models through that. I’ll probably compare models through LM Studio later or, if I polish up my own GUI, maybe just with llama.cpp.

I will be looking at the Q4 version of the model I’m using to see if that allows me to open up a much larger context length - but even Q4 for this 104B model would be too much for a 64GB machine.

After this weekend, I won’t have a lot of free time for a couple of weeks so I doubt I’ll be doing any comparing in the near future.

It all comes down to budget and use case. 64GB will still allow you to run a lot of models - 70B models at Q4 would probably be the sweet spot. I think gemma3:27B on Ollama is Q4 and comes in at just 17GB. I’d imagine that would run fine on the base spec Studio (with 36GB RAM) if that’s of interest.

As for Mistral, I see the 123B model of Mistral Large 2 (not Mistral 3.1) on Ollama at Q4 shows 77GB. It might be fun to try a comparison of 123B parameters at Q4 vs 104B parameters at Q6 on my 128GB. I’ve not seen Mistral 3 yet.

The additional benefit of the 128GB RAM is that it allows you to have multiple apps running even when the LLM is a large model (say, 70B). If you won’t be doing much of that, then it’s a non-issue.

As you can tell by this rambling post, I haven’t compared models much right now. My only comparisons have been over the last few months on my 24GB MacBook Pro.

One aside - if you’re looking at using large models, consider your SSD size. With LLMs and image models, the 1TB on my MacBook Pro started to fill up quickly (so 512GB would have been a problem). I couldn’t go higher than 1TB on my Studio, but I’ve been storing most of my models on a couple of external 1TB SSDs. LM Studio, Msty, and llama.cpp are happy to use them from the external SSD (but consider initial load-up times if your external drive is slow). Once the model is loaded into memory, where they came from is not an issue. Even when a model is “unloaded”, it's stored in Cached Files for as long as you’re not doing much else so there’s no big delay when running subsequent queries.

One aside - if you’re looking at using large models, consider your SSD size. With LLMs and image models, the 1TB on my MacBook Pro started to fill up quickly (so 512GB would have been a problem). I couldn’t go higher than 1TB on my Studio, but I’ve been storing most of my models on a couple of external 1TB SSDs. LM Studio, Msty, and llama.cpp are happy to use them from the external SSD (but consider initial load-up times if your external drive is slow). Once the model is loaded into memory, where they came from is not an issue. Even when a model is “unloaded”, it's stored in Cached Files for as long as you’re not doing much else so there’s no big delay when running subsequent queries.

I had to sacrifice SSD size to afford the ram upgrade in my Studio. Luckily an external NVMe works super quick, I can load large models in a couple of seconds.

I’m just using a couple of Crucial X9 Pro 1TB SSDs. As they’re mostly for loading LLM models, I only notice the speed when I’m waiting for 85GB to load into RAM.I had to sacrifice SSD size to afford the ram upgrade in my Studio. Luckily an external NVMe works super quick, I can load large models in a couple of seconds.

Just an update:

I’ve recently done some testing on the Qwen models.

My test run is a lengthy system prompt covering the general background to my stories. The prompt is to summarise and list key moments from an .md file that I attach to the prompt.

I first tried the non-MLX version of Qwen3-235B-A22B-UD-Q2_K_XL - a 2bit model of the 235B parameter Qwen3. This is about 88GB.

Results:

Scene 1 (1,708 words): Thinking 26.24sec • 13.04 tok/sec • 1201 tokens • 37.52s to first token

Scene 2 (1,545 words): Thinking 44.55sec • 10.78 tok/sec • 1330 tokens • 60.33s to first token

Scene 3 (3,404 words): Thinking 50.75sec • 8.22 tok/sec • 1294 tokens • 135.81s to first token

Memory Used: ~103.6GB

Cached Files: ~14.39GB

Today, I downloaded the MLX version of Qwen3-235B-A22B-3bit. This is about 104GB (the non-MLX version is closer to 111GB).

At first this one fails (“…requires 98089 MB which is close to the maximum recommended size of 98304 MB.”), but using something like sudo sysctl iogpu.wired_limit_mb=107520 enables it to run.

Result:

Scene 4 (~3,000 words): Thinking 13.33 sec. • 26.20 tok/sec • 887 tokens • 18.17s to first token

When I asked it a specific question about the scene, I got:

Thinking 13.71sec • 25.49 tok/sec • 1066 tokens • 24.24s to first token

At first I thought this model would not work, due to tight RAM constraints or, if it did, that it’d be slower than the smaller Q2 version, but I was impressed by its speed of both thinking and output.

With a smaller test prompt (no system prompt or scene), it generated: 30.89 tok/sec • 220 tokens • 4.43s to first token

The only “potential” difference in the two tests is that, although I closed all apps prior to running the Q2 test, I only used the “sudo purge” command on the Q3 test. I don’t know how much difference that might have made.

With LM Studio, the model stays in memory until you close or eject it. Activity Monitor is currently showing 119GB memory used (I have a few small apps running as well as LM Studio), with 12GB in cached files, and 84MB swap (I usually see 0 swap, so I’m not sure what that is). Memory pressure is green.

I’ve recently done some testing on the Qwen models.

My test run is a lengthy system prompt covering the general background to my stories. The prompt is to summarise and list key moments from an .md file that I attach to the prompt.

I first tried the non-MLX version of Qwen3-235B-A22B-UD-Q2_K_XL - a 2bit model of the 235B parameter Qwen3. This is about 88GB.

Results:

Scene 1 (1,708 words): Thinking 26.24sec • 13.04 tok/sec • 1201 tokens • 37.52s to first token

Scene 2 (1,545 words): Thinking 44.55sec • 10.78 tok/sec • 1330 tokens • 60.33s to first token

Scene 3 (3,404 words): Thinking 50.75sec • 8.22 tok/sec • 1294 tokens • 135.81s to first token

Memory Used: ~103.6GB

Cached Files: ~14.39GB

Today, I downloaded the MLX version of Qwen3-235B-A22B-3bit. This is about 104GB (the non-MLX version is closer to 111GB).

At first this one fails (“…requires 98089 MB which is close to the maximum recommended size of 98304 MB.”), but using something like sudo sysctl iogpu.wired_limit_mb=107520 enables it to run.

Result:

Scene 4 (~3,000 words): Thinking 13.33 sec. • 26.20 tok/sec • 887 tokens • 18.17s to first token

When I asked it a specific question about the scene, I got:

Thinking 13.71sec • 25.49 tok/sec • 1066 tokens • 24.24s to first token

At first I thought this model would not work, due to tight RAM constraints or, if it did, that it’d be slower than the smaller Q2 version, but I was impressed by its speed of both thinking and output.

With a smaller test prompt (no system prompt or scene), it generated: 30.89 tok/sec • 220 tokens • 4.43s to first token

The only “potential” difference in the two tests is that, although I closed all apps prior to running the Q2 test, I only used the “sudo purge” command on the Q3 test. I don’t know how much difference that might have made.

With LM Studio, the model stays in memory until you close or eject it. Activity Monitor is currently showing 119GB memory used (I have a few small apps running as well as LM Studio), with 12GB in cached files, and 84MB swap (I usually see 0 swap, so I’m not sure what that is). Memory pressure is green.

I’ve recently been focussing on image generation models. I’ll update this thread when I get the chance.@JSRinUK have you done any further testing with newer models, or models specifically for coding?

Any experience with Flux 2 or Qwen-Image?I’ve recently been focussing on image generation models. I’ll update this thread when I get the chance.

Flux.2 is a bit heavy for 128GB right now, so I’ve been looking at Flux.1 and variants, Qwen-Image-2512, Qwen-Image-Edit-2511, ZImage-Turbo, etc.Any experience with Flux 2 or Qwen-Image?

I stepped away from local LLM for a little while. Once you’ve tested the big models, you need to have a real use for them to use them in earnest. For me it’s mostly about brainstorming my stories and, once you have your preferred model, you’re kind of already there.

I did do some “coding tests” a little while back in which I pitted frontier AI against large LLMs on my Mac. The results were not much to write about. The local LLMs pretty much failed. They would generate code, but the code would then generally fail. They create the functions you need for your code to work, but then don’t call them - because they’ve forgotten about them by the time it needs to use them. They may have long context, but they have short memory.

Even frontier AI didn’t fare much better. They’re generally so quick to go down the “popular path” of coding, that they trip right up when you tell them “I have a Mac, not CUDA-core stuff”.

You could work with the frontier AI, but you’d find yourself constantly returning to it with errors - often silly things that, if you already know a bit about coding, you can fix yourself. Sometimes it felt like I was teaching the AI - at which point, I’d call the test a failure.

The only one that showed any sign of help (despite not being completely flawless) was Claude Sonnet - I didn’t have Opus at the time (I do now).

Instead, I recently shifted my focus to image generation. As with local LLM, my primary goal is that everything should remain local - no “calling out to the web” once the models are downloaded. I had a poor experience with the “node hell” that was ComfyUI several months ago, so I’m avoiding that for now.

Instead, I’ve been leveraging https://pypi.org/project/mflux/ which is an MLX port of several generative image models.

Mflux supports the following models:

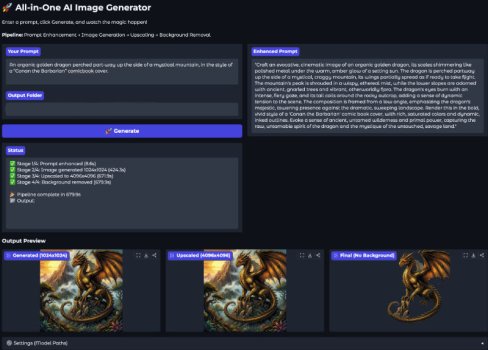

With the help of Claude doing (most of) the coding, I’ve assembled an “image generation toolkit”, which consists of the following python “apps”:

It’s amazing what we can do on a desktop computer these days.

I did do some “coding tests” a little while back in which I pitted frontier AI against large LLMs on my Mac. The results were not much to write about. The local LLMs pretty much failed. They would generate code, but the code would then generally fail. They create the functions you need for your code to work, but then don’t call them - because they’ve forgotten about them by the time it needs to use them. They may have long context, but they have short memory.

Even frontier AI didn’t fare much better. They’re generally so quick to go down the “popular path” of coding, that they trip right up when you tell them “I have a Mac, not CUDA-core stuff”.

You could work with the frontier AI, but you’d find yourself constantly returning to it with errors - often silly things that, if you already know a bit about coding, you can fix yourself. Sometimes it felt like I was teaching the AI - at which point, I’d call the test a failure.

The only one that showed any sign of help (despite not being completely flawless) was Claude Sonnet - I didn’t have Opus at the time (I do now).

Instead, I recently shifted my focus to image generation. As with local LLM, my primary goal is that everything should remain local - no “calling out to the web” once the models are downloaded. I had a poor experience with the “node hell” that was ComfyUI several months ago, so I’m avoiding that for now.

Instead, I’ve been leveraging https://pypi.org/project/mflux/ which is an MLX port of several generative image models.

Mflux supports the following models:

- Z-Image Turbo,

- Flux.1 (including variants),

- FIBO,

- SeedVR2

- Qwen-Image (including Qwen-Image-Edit).

With the help of Claude doing (most of) the coding, I’ve assembled an “image generation toolkit”, which consists of the following python “apps”:

- Prompt Workshop

- This sends your simple prompt (eg. “a helicopter hovering over a hot dog stand”) and leverages a local LLM to enhance it into something more elaborate, to assist the Image Generation model. I’m using a VLM so that I can also include an image, and the “enhanced prompt” will use that as a reference (colours, style, cinematography, etc)

- A second function of this app is simply to have a local LLM describe what it sees in an image I provide. So, if there's an image I like and I want to generate it elsewhere with some modifications, this will assist me with that.

- Multi-Model Image Generator

- The intention here is to take my image generation prompt and generate the image. I can select the size I want, plus alter other parameters, and whatever quantity of images I want (with the seed varying).

- I can also select from up to 6 different image generation models (all the ones mflux supports, but not Flux.2 yet), so that I can select my favourite.

- Multi-Model Image Editor

- Here, I provide one or two images and describe what I want to change in the image.

- I can select from up to 2 different image editing models. If the chosen model can accept both images, it'll use them. Otherwise it'll work on just the first image.

- Image Upscaler

- This does what it says on the tin. I provide an image, pick a size or scale factor, and I'm provided with an upscaled version of the image.

- Background Remover

- A new addition to the toolbox. I provide an image, and within a few seconds, it creates the same image with the background removed (or with a plain black, or plain white background). Optionally, the mask is also generated (which could be useful if I wanted to edit in a graphics app).

It’s amazing what we can do on a desktop computer these days.

Attachments

Last edited:

For my own amusement, I did a couple of LLM comparisons today (I’ve been playing about with my Raspberry Pi 500+). These results are, by no means definitive (I didn’t use the same LLM or software), I just tried out some under 1B parameter models.

I used the same prompt on each machine.

Raspberry Pi 500+ (16 GB RAM), using llama.cpp and Qwen3-0.6B-Q4_K_M.gguf (4 threads, 2048ctx): ~15 tok/sec

Microsoft Surface Pro 6 (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM, Win11), using LM Studio and Qwen3-0.6B-Q8_0: ~9 tok/sec (iGPU); ~18 tok/sec (CPU only)

MacBook Pro (M4 Pro, 24GB RAM), using LlamaBarn and Gemma-3-1B: ~189 tok/sec

Mac Studio (M4 Max, 128GB RAM), using LlamaBarn and Gemma-3-1B: ~257 tok/sec

mflux only supports these two variants: flux2-klein-4b and flux2-klein-9b. My initial tests at producing a 1024x1024 image measured approximately 28s for the 4B and 38s for the 9B - however, in mitigation, it looked like it took about 10-12 seconds to load up from the external SSD first so the "real times" are a little less than that.

I used the same prompt on each machine.

Raspberry Pi 500+ (16 GB RAM), using llama.cpp and Qwen3-0.6B-Q4_K_M.gguf (4 threads, 2048ctx): ~15 tok/sec

Microsoft Surface Pro 6 (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM, Win11), using LM Studio and Qwen3-0.6B-Q8_0: ~9 tok/sec (iGPU); ~18 tok/sec (CPU only)

MacBook Pro (M4 Pro, 24GB RAM), using LlamaBarn and Gemma-3-1B: ~189 tok/sec

Mac Studio (M4 Max, 128GB RAM), using LlamaBarn and Gemma-3-1B: ~257 tok/sec

Today I've been working on adding Flux.2-Klein-9B to my text2image code. It took some time to get it sorted (mainly due to wanting to manually download the files to my external SSD as my internal drive is getting a bit full).Any experience with Flux 2 or Qwen-Image?

mflux only supports these two variants: flux2-klein-4b and flux2-klein-9b. My initial tests at producing a 1024x1024 image measured approximately 28s for the 4B and 38s for the 9B - however, in mitigation, it looked like it took about 10-12 seconds to load up from the external SSD first so the "real times" are a little less than that.

I stepped away from local LLM for a little while. Once you’ve tested the big models, you need to have a real use for them to use them in earnest. For me it’s mostly about brainstorming my stories and, once you have your preferred model, you’re kind of already there.

Agreed.

Most of the smaller models work fine for the average user. For me, it's having LM Studio always running in the background, and having large context for when I need it. Even with a 18GB model, and 32k context buffer, it eats up a significant amount of unified memory. I do want to setup a couple devices to offload their AI processing to the Mac Studio, so having LMS running in the background lets me do that.

Register on MacRumors! This sidebar will go away, and you'll see fewer ads.